Chicago tops list of most dangerous cities for migrating birds

By Pat Leonard

An estimated 600 million birds die from building collisions every year in the U.S., and research from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology offers one explanation for it.

A team led by Kyle Horton, a Rose postdoctoral fellow at the lab, ranked metropolitan areas where, due to a combination of light pollution and geography, birds are at the greatest risk of becoming attracted to and disoriented by lights and crashing into buildings.

Among their findings: While migration routes vary depending on the season, the same three large cities in the central U.S. – Chicago, Houston and Dallas – top both the spring and autumn lists of most dangerous for migrating birds.

“Those three cities are uniquely positioned in the heart of North America’s most trafficked aerial corridors. This, in combination with being some of the largest cities in the U.S., makes them a serious threat to the passage of migrants, regardless of season,” Horton said.

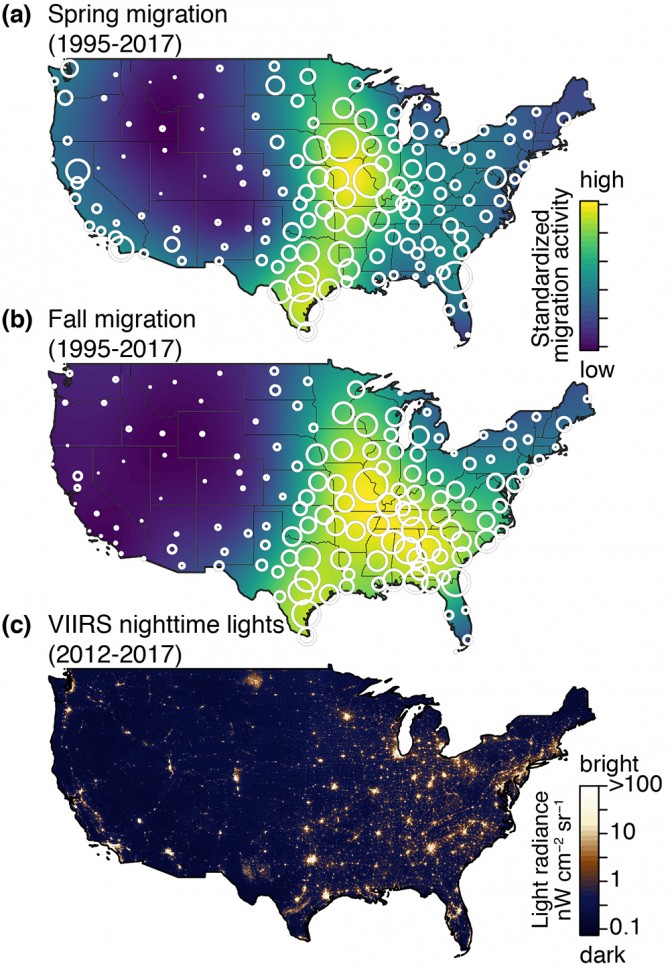

Research associate Andrew Farnsworth is senior author of “Bright Lights in the Big Cities: Migratory Birds’ Exposure to Artificial Light,” published April 1 in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. The work combines satellite data showing light pollution levels with weather radar data measuring bird migration density.

Because many birds alter their migrations routes between spring and fall, rankings of the most dangerous cities change slightly with the seasons. During spring migration, billions of birds pass through the central U.S. between the Rockies and the Appalachians, so cities primarily in the middle of the country comprise the most-dangerous list for that season. Heavy spring migration bird traffic along the West Coast also puts Los Angeles on the spring most-dangerous list.

Fall bird migration tends to be intense along the heavily light-polluted Atlantic seaboard, which is why four eastern cities make the list in autumn.

Although bird migration in spring and fall lasts for months, the heaviest migratory activity occurs during the span of just a few days. For example, a top-ranked light-polluting city can expect half of its bird migration traffic to pass through over seven nights spaced out during the season; these nights are unique for each city and depend upon wind conditions, temperature and timing.

Campaigns such as Audubon’s Lights Out encourage cities to reduce lights from building windows on heavy migration nights to reduce bird mortality.

“Now that we know where and when the largest numbers of migratory birds pass heavily lit areas, we can use this to help spur extra conservation efforts in these cities,” said study co-author Cecilia Nilsson, also a Rose postdoctoral fellow at the Lab of Ornithology. “For example, Houston Audubon uses bird migration forecasts from the Lab’s BirdCast program to run ‘lights out’ warnings on nights when big migratory movements are expected over the city.”

Horton also notes that, because an estimated quarter-million birds die from collisions with houses and residences every year, even homeowners in these most dangerous metro areas for migrating birds can play an important role. “If you don’t need lights on, turn them off,” Horton said. “It’s a large-scale issue, but acting even at the very local scale to reduce lighting can make a difference.”

Also contributing were research associate Frank La Sorte and postdoctoral researcher Adriaan Dokter of the Lab of Ornithology, and Benjamin Van Doren ’16, now a doctoral student at Oxford University.

Support for this study came from the Edward W. Rose Postdoctoral Fellowship, Marshall Aid Commemoration Commission, the Leon Levy Foundation and the National Science Foundation.

Pat Leonard is a staff writer at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe